Cano-Díaz Ana Luz1, Pérez-Barragán Edgar1, Triana-González Salma1, Salinas-Velázquez Gloria Elizabeth2, Rodríguez-Evaristo Mara Soraya3, Mata-Marín José Antonio1, Gaytán-Martínez Jesús Enrique1.

- Infectious Diseases Department, Hospital de Infectología “La Raza” National Medical Center, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico City, México.

- Imagenology Department, Hospital de Infectología “La Raza” National Medical Center, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico City, México.

- Internal medicine Department, Hospital de Especialidades “La Raza” National Medical Center, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico City, México.

Correspondence author: José Antonio Mata Marín (jamatamarin@gmail.com)

Address: Hospital de Infectología “La Raza” National Medical Center. Seris y Vallejo S/N. Colonia La Raza. Postal code: - Delegación Azcapotzalco, Mexico.

Phone: (55)57245900 ext 23924, jamatamarin@gmail.com

Incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in antiretroviral therapy-naïve patients living with HIV who start a regimen with DTG/ABC/3TC compared to those who start BIC/FTC/TAF at 48-week follow-up at the Hospital de Infectología CMN “La Raza”: a preliminary analysis.

Introduction: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most frequent chronic liver disease. Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI) are risk factors for NAFLD development. The aim of this study was to determine NAFLD incidence by non-invasive methods in patients living with HIV (PLHIV) naïve to antiretroviral therapy starting with dolutegravir (DTG) regimen compared with bictegravir (BIC) regimen after 48 weeks of follow-up.

Material and methods: Prospective cohort of PLHIV from February 2020 to December 2022. NAFLD incidence was calculated with TyG, FLI, HSI indexes and hepatic US and elastography baseline and at 48 weeks between BIC-group and DTG-group. Relative risk for NAFLD was calculated.

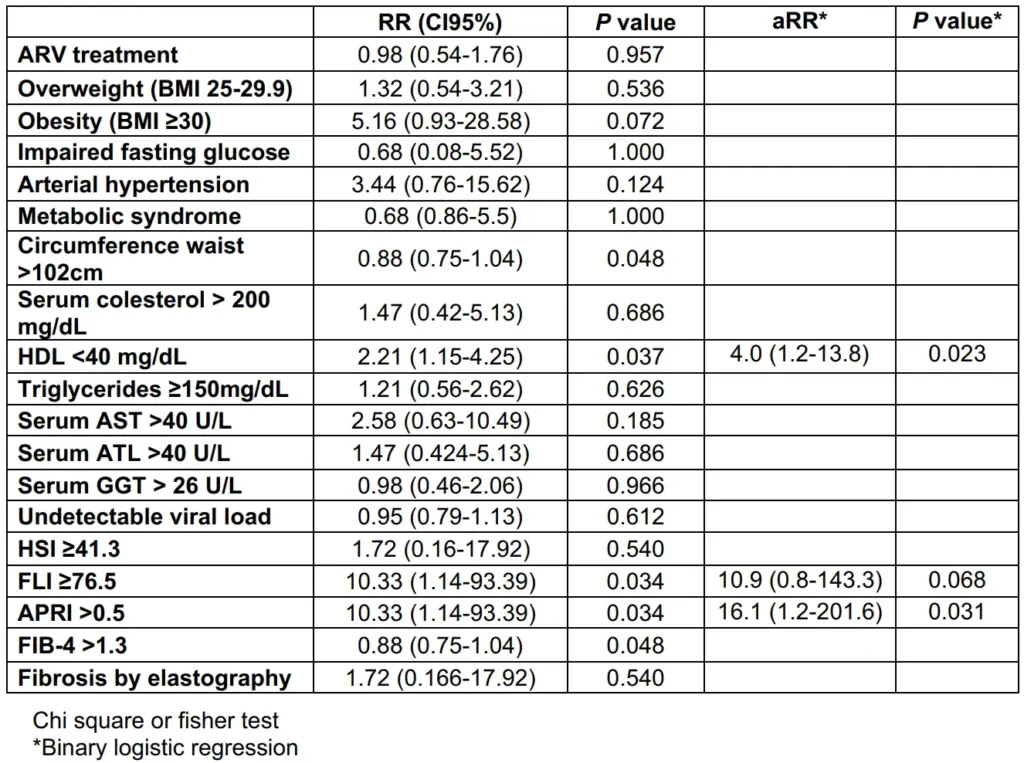

Results: 80 men PLHIV were included, median age was 26 (IQR 23-30) years old. NAFLD incidence was 8.8%. At 48 weeks, TyG in DTG-group was 4.69 (4.44-4.88) vs 4.48 (4.32-4.68) in BIC-group (p=0.008), HSI in DTG-group 33.35 (29.7-36.5) vs 30.45 (28.25-33.45) in BIC-group (p=0.017), and FLI in DTG-group was 20.97 (9.92-46.96) vs 12.34 (6.71-28.28) in BIC-group (p=0.035). Risk factors for NAFLD were HDL-c <40 mg/dL aRR 4.0 (1.2-13.8; p=0.023) and APRI >0.5 aRR 16.1 (1.2-201.6; p=0.031).

Conclusions: The study found no significant difference in NAFLD incidence between PLHIV treated with BIC and DTG. However, low levels of HDL-c and APRI >0.5 were identified as risk factors for NAFLD/NASH in this population.

Keywords: NAFLD, HIV, second generation INSTI, dolutegravir, bictegravir.

Incidencia de enfermedad por hígado graso no alcohólico en pacientes que viven con VIH no experimentados a terapia antirretroviral que inician un régimen con DTG/ ABC/3TC comparado con los que inician BIC/FTC/TAF a las 48 semanas de seguimiento en Hospital de Infectología CMN “La Raza”: Un análisis preliminar

Introducción: la enfermedad por hígado graso no alcohólica (EHGNA) es la causa más frecuente de cirrosis. Los INSTI se consideran factor de riesgo para su desarrollo. Determinar la incidencia de EHGNA por métodos no invasivos en pacientes que viven con VIH (PVVIH) sin terapia antirretroviral (TARV) que inician con DTG/ABC/3TC comparado con BIC/FTC/TAF a 48 semanas de seguimiento.

Material y métodos: cohorte prospectiva de febrero 2020 a diciembre 2022. La incidencia de EHGNA se calculó con TyG, FLI, HSI, ultrasonido hepático (US) y elastografía, basal y a 48 semanas en PVVIH que inician BIC vs DTG. Se midió riesgo relativo para el desarrollo de EHGNA.

Resultados: se incluyeron 80 PVVIH, hombres, mediana de 26 años (IQR 23-30). La incidencia fue 8.8%. A 48 semanas TyG fue de 4.69 (4.44-4.88) con DTG vs 4.48 (4.32-4.68) con BIC (p=0.008), HSI en DTG 33.35 (29.7-36.5) vs 30.45 (28.25-33.45) en BIC (p=0.017) y FLI con DTG 20.97 (9.92-46.96) vs 12.34 (6.71-28.28) con BIC (p=0.035). Los factores de riesgo para EHGNA fueron HDL-c <40 mg/dL aRR 4.0 (1.2-13.8; p=0.023) y APRI >0.5 aRR 16.1 (1.2-201.6; p=0.031).

Conclusiones: no hubo diferencia en la incidencia de EHGNA en BIC vs DTG. HDL-c and APRI >0.5 fueron factores de riesgo para su desarrollo.

Palabras clave: EHGNA, VIH, INSTI de segunda generación, dolutegravir, bictegravir.

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as the histological presence of steatosis in >5% hepatocytes and is the most frequent chronic liver disease worldwide, with a prevalence estimated to be between 17% and 46% in the general population. In Mexico, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has become the leading cause of cirrhosis since 2012, with an incidence of 36% in 2019. Steatohepatitis (NASH) can progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys conducted in Mexico in 2018-19 (ENSANUT 2018-19) revealed an increase in obesity rates from 25% in 2000 to 36% in 2019. There is a correlation between body mass index (BMI), the grade of steatosis, and the severity of the hepatic lesion. Weight gain and an increased incidence of obesity (12.3%) have been observed in individuals treated with antiretrovirals (ARV) containing dolutegravir (DTG). Significantly more weight gain was observed with DTG-containing regimens, particularly in combination with tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF).

People living with HIV (PLHIV) generally have a higher degree of liver fibrosis compared to individuals without HIV. The controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) values were higher in PLHIV with low CD4+ cell counts and longer exposure to integrase inhibitors (INSTIs). Abdominal ultrasound (US) has a higher sensitivity for diagnosing NAFLD in PLHIV, and there are now validated noninvasive serological tests for NAFLD diagnosis in PLHIV, such as the fatty liver index (FLI), hepatic steatosis index (HSI), and triglyceride and glucose index (TyG).

The objective of this study was to determine the incidence of NAFLD using non-invasive methods in treatment-naïve PLHIV starting with a DTG-containing regimen compared to a bictegravir (BIC)-containing regimen after 48 weeks of follow-up.

Methods

Design

A prospective cohort with patients treated in HIV clinic at Hospital de Infectología “La Raza” National Medical Center, Mexico City, enrolled from February 2020 to December The HIV clinic is a third level reference center for people with social security coverage. Only male patients are attended in this part of the clinic, this study was approved by the local committee for health research 0350 at the Hospital de Infectología “La Raza” National Medical Center with approved registration number R-2021-3502-084. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The cohort is nested in an open-label randomized clinical trial, comparing BIC/FTC/TAF with DTG/3TC/ABC in patients with HIV type 1 (HIV-1) infection starting antiretroviral treatment (ART).

Study population

Study subjects were men living with HIV naïve to ART, ≥18 years old. Patients were excluded if they have autoimmune or genetic liver disease, previous diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol consumption greater than 30 g/day (14 standard drinks), AUDIT score ≥ 16 points, or coinfection with hepatitis B or C virus.

Measurements

Baseline examinations performed were anthropometric measurements, including waist and hip circumference, using a plastic tape measure. Vital signs were also recorded. Bioimpedance measurements were taken using the “body complete beurer BF105 model” equipment, which included weight, water content, body fat percentage, and bone mass in kilograms. Various blood tests were conducted, including complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, liver function tests, lipids, HIV-1 RNA viral load, CD4+ cell count, and general urine analysis. The AUDIT score, as well as serology for hepatitis B and C, were also assessed. Additionally, quantitative ultrasound elastography methods were used, including transient elastography and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) techniques, using the QelaXto equipment and a multi-frequency convex transducer for ultrasound measurements.

We calculated the triglycerides/glucose index (TyG), fatty liver index (FLI), hepatic steatosis index (HSI), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI), and fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) at baseline and at 48 weeks. This was done to determine the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD/NASH) in people living with HIV (PLHIV) who started antiretroviral treatment (ART) with bictegravir 50mg/tenofovir alafenamide fumarate 25 mg/emtricitabine 200mg (BIC/FTC/TAF) compared to dolutegravir 50 mg/abacavir 600 mg/lamivudine 300 mg (DTG/3TC/ABC).

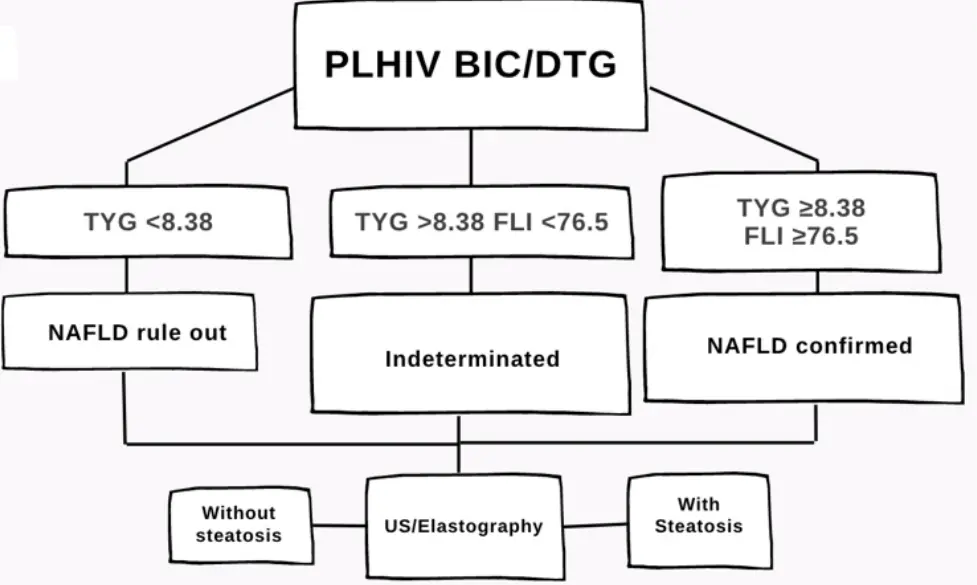

NAFLD was defined in this cohort as TyG ≥8.38 and FLI ≥76.5, in case of TyG <8.38 and FLI <76.5 the diagnosis was supported by steatosis identification by US and measurement of the degree of fibrosis by elastography with a median result of 10 measurements with the elastography realized by the same person (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated with a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80% using a formula for finite sample size. It resulted in 142 patients in each group of INSTI, based on a prevalence of NAFLD study (Castro-Martínez MG et al.) (9). Descriptive results were summarized using the median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for variables with a non-normal distribution.

The incidence rate of NAFLD/NASH during the first 48 weeks of treatment was calculated using the TyG and FLI indices, as well as hepatic ultrasound (US) results (Figure 1). A comparison of the median values of the TyG index, FLI, HSI, APRI, FIB-4, and hepatic US and elastography results at 48 weeks was conducted between the BIC-group and DTG-group using the Mann Whitney U-test.

To determine the relative risk of developing NAFLD, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used with the collected variables. In cases where statistically significant results were obtained, binary logistic regression was conducted to adjust for relative risk (RR). A p-value ≤ 0.05 with a confidence interval of 95% was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Version 20.0 program.

Results

The preliminary analysis was conducted with 80 patients, all of whom were men living with HIV, with a median age of 26 years (IQR 23-30). The median AUDIT score was 3 (2-6). The baseline TyG, HSI, and FLI indexes did not exceed the estimated cut-off points for NAFLD/NASH.

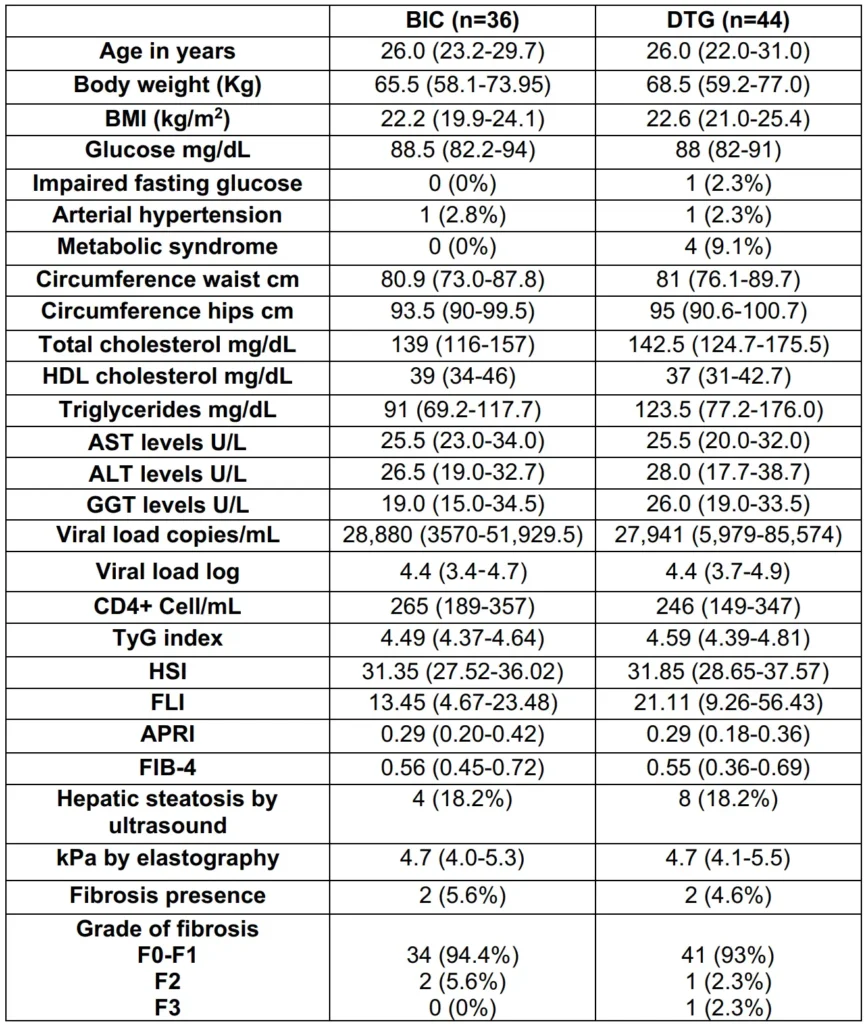

In the BIC-group, the TyG, HSI, and FLI indexes were 4.49 (4.37-4.64), 31.35 (27.52-36.02), and 13.45 (4.67-23.48), respectively. In the DTG-group, the TyG index was 4.59 (4.39-4.81), HSI was 31.85 (28.65-37.57), and FLI was 21.11 (9.26-56.43), respectively.

Regarding the biochemical predictors for liver fibrosis, the median values of APRI were 0.29 (0.20-0.42) in the BIC-group and 0.29 (0.18-0.36) in the DTG-group. The FIB-4 index was 0.56 (0.45-0.72) in the BIC-group and 0.55 (0.36-0.69) in the DTG-group.

At baseline, hepatic ultrasound revealed 12 patients (15%) with hepatic steatosis (4 in the BIC-group and 8 in the DTG-group), and 4 patients (5%) had fibrosis, with 2 in each group. The baseline median HIV-1 RNA viral load was 27,941 copies/mL (5349-67825), and the CD4+ cell count was 247 cel/mm3 (174-353) (Table 1).

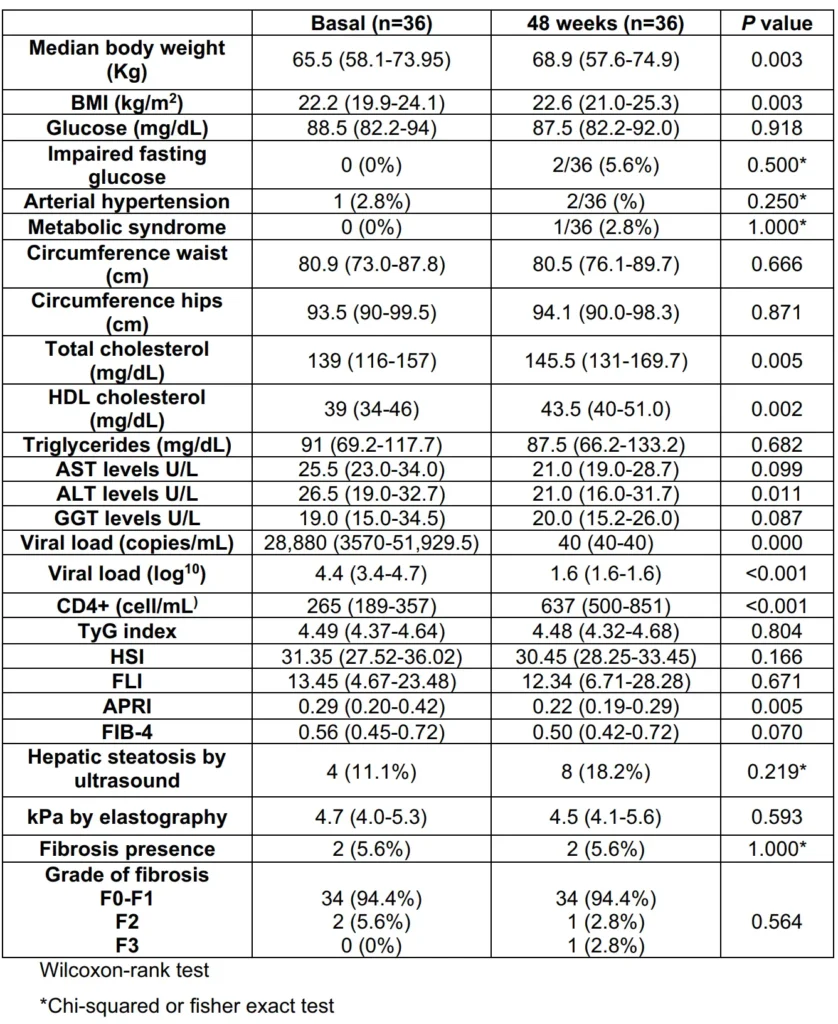

After 48 weeks of treatment with any INSTI in the study, the incidence of NAFLD was 8.8%. In the BIC-group at 48 weeks compared to baseline, the values were as follows: TyG 4.48 (4.32-4.68; p=0.804), HSI 30.4 (28.2-33.4; p=0.166), FLI 12.3 (6.71-28.28; p=0.671), APRI 0.22 (0.19-0.29; p=0.005), and FIB-4 0.50 (0.42-0.72; p=0.070).

At baseline, 4 patients (11.1%) had steatosis identified by ultrasound, and after 48 weeks of treatment, 8 patients (18.2%) had steatosis identified by ultrasound (p=0.219). The median kPa value measured by elastography at 48 weeks was 4.5 kPa (4.1-5.6; p=0.593). Two patients (5.6%) had fibrosis, with one classified as F2 and one as F3 (Table 2).

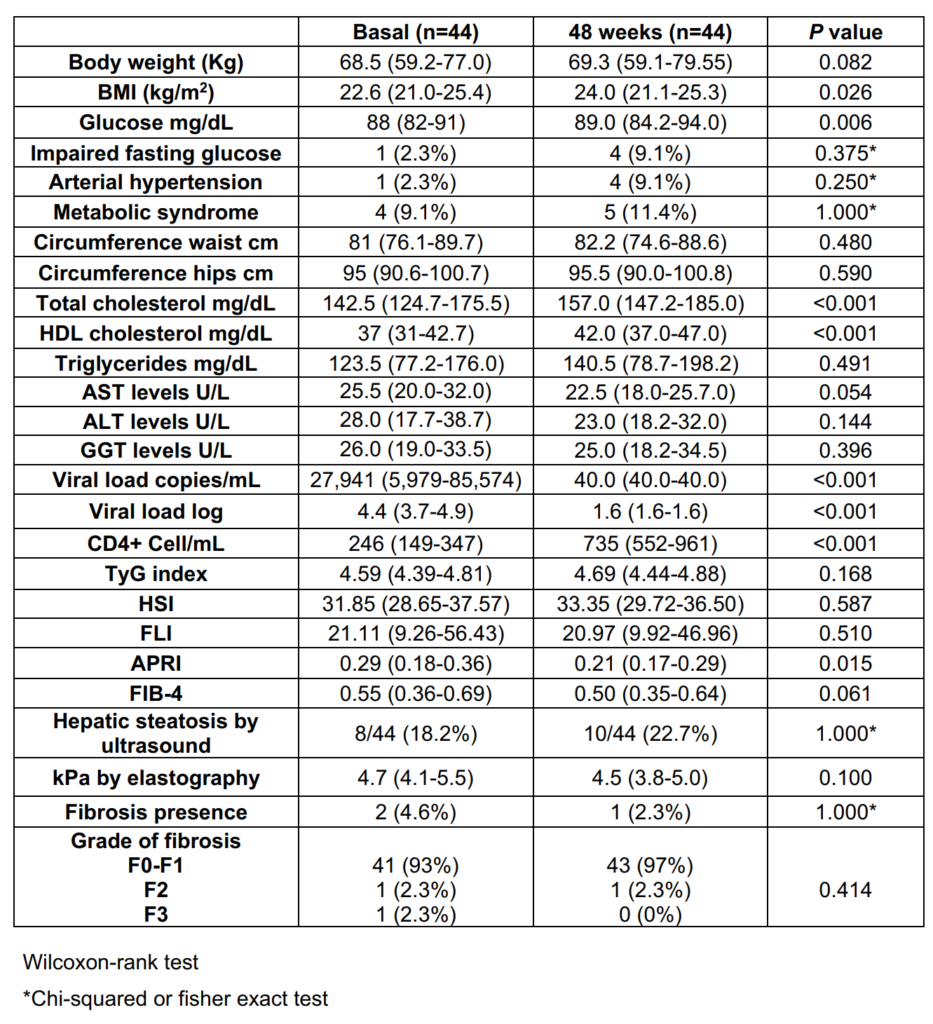

In the DTG-group, compared to baseline, the values at 48 weeks of treatment were as follows: TyG median 4.69 (4.44-4.88; p=0.168), HSI 33.35 (29.7-36.5; p=0.587), FLI 20.97 (9.92-46.96; p=0.510), APRI 0.21 (0.17-0.29; p=0.015), and FIB-4 0.50 (0.35-0.64; p=0.061). Ten patients (22.7%) had steatosis identified by ultrasound at 48 weeks (p=0.705), and 1 patient (2.3%) had fibrosis (F2) detected by elastography (p=0.564). The median kPa value measured by elastography at 48 weeks was 4.5 kPa (3.8-5.0; p=0.100) (Table 3).

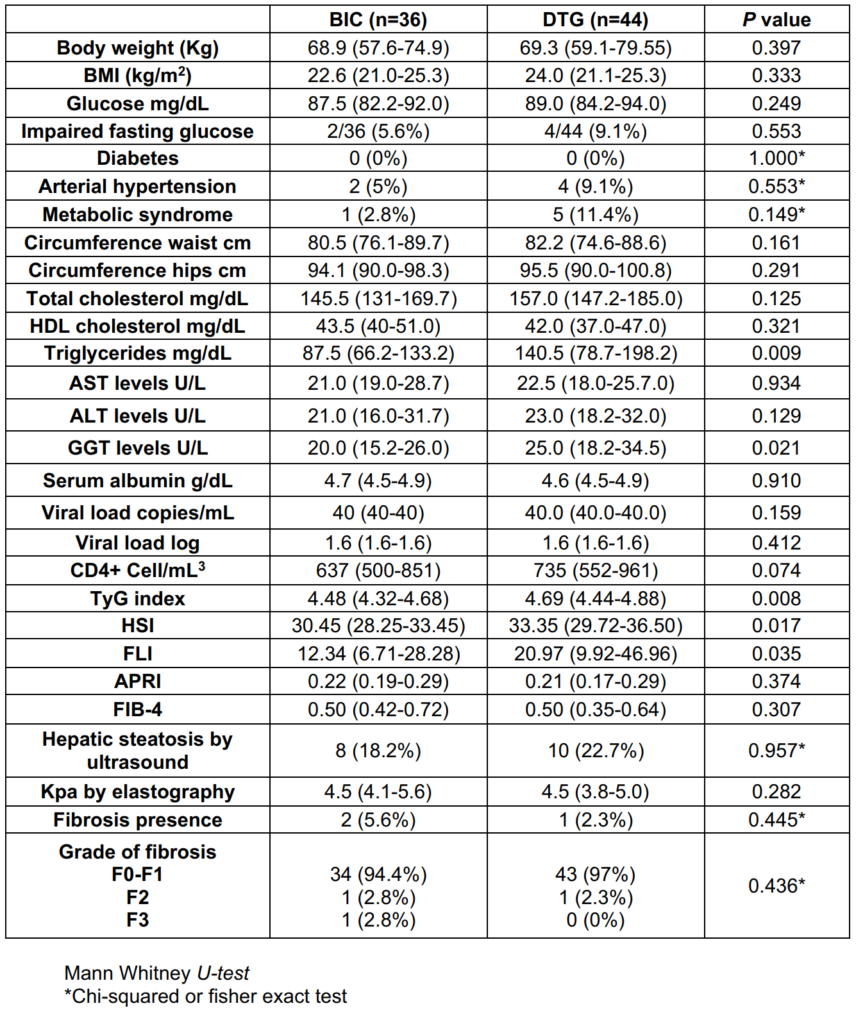

When NAFLD/NASH indexes were compare between groups at 48 weeks, TyG in DTG-group was 4.69 (4.44-4.88) vs 4.48 (4.32-4.68) in BIC-group (p=0.008), HSI in DTGgroup 33.35 (29.7-36.5) vs 30.45 (28.25-33.45) in BICgroup (p=0.017) and FLI in DTG-group was 20.97 (9.92- 46.96) vs 12.34 (6.71-28.28) in BIC-group (p=0.035). APRI was 0.21 (0.17-0.29) vs 0.22 (0.19-0-29) (p=0.374) in DTG and BIC-group respectively, FIB-4 was 0.50 (0.42-0.72) in BIC-group and 0.50 (0.35-0.64) in DTG-group (p=0.307). Hepatic steatosis by US at 48 weeks was 8 (18.2%) and 10 (22.7%) (p=0.957) in BIC and DTG group respectively, hepatic fibrosis was present in 2 (5.6%) patients in BIC-group vs 1 (2.3%) in DTG-group (Table 4).

Risk factors associated with an increase in developed of NAFLD/NASH found in this cohort were HDL-c <40 mg/ dL (RR 2.21; 95% CI, 1.15-4.25), FLI ≥76.5 (RR 10.3; 95% CI, 1.1-93.3) and APRI ≥0.5 (RR 10.3; 95% CI, 1.1-93.3). After adjustment in a logistic regression model only HDL-c <40 mg/dL 4.0 (1.2-13.8; p=0.023) and APRI >0.5 16.1 (1.2-201.6; p=0.031) were significant (Table 5).

Discussion

In this preliminary analysis of 80 PLHIV without viral chronic hepatitis and 48 weeks of ART there was a low incidence of NAFLD/NASH diagnosed by TyG, HSI, FLI indexes and US. We did not find differences when we compared DTGgroup with BIC-group. APRI >0.5 and HDL-c <40 mg/dL were the only risk factors associated with development of NAFLD/NASH. The DTG-group had higher levels of triglycerides, GGT, TyG, HSI and FLI at 48 weeks of treatment, although levels were not higher than cutoff levels.

Different to reported by Bischoff et al., who had NAFLD incidence in half of participants we had an incidence of 8.8% NAFLD in PLHIV. They found an association between use of TAF and INSTI with more rapid progression of steatosis in PLHIV, similar to Kirkegaard, which reported than the use of INSTI was associated with higher odds to hepatic steatosis. They also reported factors like male gender, higher BMI, and higher serum ALT, weight, cholesterol, fasting glucose, HDL-c, AST with increase and progression in NAFLD/ NASH; however, in these studies patients were older with more time of HIV diagnosis and longer time of ART. (6, 10, 11) Maurice reported a higher prevalence of NAFLD/NASH in PLHIV and also found more develop of these with higher biochemical markers. (12)

Our results are different from those reported by Arenzana et al., which found more NAFLD with higher levels of TyG, FLI and HSI cut off than these study, it could be because they performed CAP and their population had more time of ART. (13)

Increase in gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), abdominal circumference, BMI, cholesterol, triglycerides, AST and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) have been associated with presence, developed and progression of NAFLD; in concordance with other studies we found a significant association with HDL-c <40 mg/dL. (12,14,15,16)

Regarding liver fibrosis progression, Fourman et al., demonstrated that individuals with a greater amount of visceral fat accumulation had a greater presence of fibrosis and progression in PLHIV, but their patients had median age higher that patients of this study, median age of HIV diagnosis in their population was 16 years with stable treatment in contrast with our population with 1 year of treatment, and more than half of their population was obese in comparison of low prevalence of obesity in our patients. (17)

Limitations in this study were that it is an open-label design, small sample size with only men included, the lack of insulin measurements and CAP, the follow-up at the moment it is only 1 year and the patients are young to develop NAFLD/NASH. The strengths of the study is that it is the first that is measuring incidence of NAFLD/NASH in Latin America in PLHIV. We were able to do an elastography to detect fibrosis, the use of non-invasive diagnostic methods to detect NAFLD/NASH at 1 year of follow-up. It is necessary to continue increasing sample size and evaluating patients with follow-up more than 1 year with second generation INSTI to detect NAFLD/NASH at more time of ART; incorporating CAP in the diagnosis strategy of NAFLD/NASH is necessary to be more accurate.

In conclusion, in this preliminary analysis there was no difference in NAFLD/NASH development in PLHIV treated with BIC vs DTG. HDL-c <40 mg/dL and APRI >0.5 are associated with NAFLD/NASH development.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the participants of this study.

Potential conflicts of interest. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1) Han SK, Baik SK, Kim MY. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Definition and subtypes [published online ahead of print, 2022 Dec 28]. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;10.3350/cmh.2022.0424. doi:10.3350/cmh.2022.0424.

2) A. Gonzalez-Chagolla, A. Olivas-Martinez, J. Ruiz-Manriquez, et al. Cirrhosis etiology trends in developing countries: transition from infectious to metabolic conditions. Report from a multicentric cohort in central Mexico. Lancet Reg Health Am, 7 (2022), p. 100151

3) Barquera S, Hernández-Barrera L, Trejo-Valdivia B, et al. (2020). Obesidad en México, prevalencia y tendencias en adultos. Salud Pública de México, 62(6), 682-692.

4) Bernal-Reyes R, Castro-Narro G, Malé-Velázquez R. et al. The Mexican consensus on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2019 Jan-Mar;84(1):69-99. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2018.11.007. Epub 2019 Jan 31. PMID: 30711302.

5) NAMSAL ANRS 12313 Study Group; Kouanfack C, Mpoudi-Etame M, Omgba Bassega P, et al. Dolutegravir-Based or Low-Dose Efavirenz-Based Regimen for the Treatment of HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 29;381(9):816-826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904340. Epub 2019 Jul 24. PMID: 31339676.

6) Venter WDF, Moorhouse M, Sokhela S, et al. Dolutegravir plus Two Different Prodrugs of Tenofovir to Treat HIV. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 29;381(9):803-815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902824. Epub 2019 Jul 24. PMID: 31339677.

7) Liu D, Shen Y, Zhang R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of metabolic associated fatty liver disease among people living with HIV in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;36(6):1670-1678. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15320. Epub 2021 Jan 19. PMID: 33140878.

8) Busca C, Sánchez-Conde M, Rico M, et al. Assessment of Noninvasive Markers of Steatosis and Liver Fibrosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Monoinfected Patients on Stable Antiretroviral Regimens. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022 Jun 9;9(7):ofac279. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac279. PMID: 35873289; PMCID: PMC9297309.

9) Castro-Martínez MG, Banderas-Lares DZ, Ramírez-Martínez JC, et al. Prevalencia de hígado graso no alcohólico en individuos con síndrome metabólico. Cir Cir [Internet]. 2012 [citado el 11 de agosto de

10) Bischoff J, Gu W, Schwarze-Zander C, et al. Stratifying the risk of NAFLD in patients with HIV under combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). EClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2021;40(101116):101116. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101116

11) Kirkegaard-Klitbo DM, Fuchs A, Stender S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of moderate-to-severe hepatic steatosis in human immunodeficiency virus Infection: The Copenhagen Co-morbidity liver study. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020;222(8):1353–62. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa246

12) Maurice JB, Patel A, Scott AJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV-monoinfection. AIDS [Internet]. 2017;31(11):1621–32. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001504

13) Busca-Arenzana C, Sánchez-Conde M, Rico M, et al. Assessment of noninvasive markers of steatosis and liver fibrosis in human immunodeficiency virus-monoinfected patients on stable antiretroviral regimens. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022;9(7):ofac279. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac279

14) Vodkin I, Valasek MA, Bettencourt R, et al. Clinical, biochemical and histological differences between HIV-associated NAFLD and primary NAFLD: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2015;41(4):368–78. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.13052

15) Fujii H, Doi H, Ko T, et al. Frequently abnormal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity is associated with future development of fatty liver: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2020;20(1):217. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01369-x

16) Neuman MG, Cohen LB, Nanau RM. Biomarkers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2014;28(11):607–18. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/757929

17) Fourman LT, Stanley TL, Zheng I, et al. Clinical predictors of liver fibrosis presence and progression in human immunodeficiency virus-associated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2021;72(12):2087–94. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa382